Discontent doesn’t mean defection

The Democratic party has spent the last year with a net favorability rating considerably worse than that of the Republican party. Yet the Democrats have had strong successes in picking up seats in the Virginia and New Jersey legislative races in 2025 and in special elections around the country. How can the more unpopular party be winning?

Here is the net favorability rating for the Democratic and Republican parties since early 2025. While both parties have had net negative ratings all year, the Democrats have been consistently worse, with a net rating hovering around -30 percentage points, except in November. Republicans by contrast have generally been around -14 with a recent decline to almost -20 points.

The one brighter moment for the Democrats was in November when their net favorability rose about 13 points and momentarily matched the GOP, before sinking again in January. The November poll was conducted during the shutdown. Democrats benefited, if briefly.

Why is the Democratic party so unpopular relative to the Republican party? Do Republicans give especially unfavorable ratings to the Democrats? Yes, of course they do. Just as Democrats deeply dislike the Republicans. Is it that independents are especially sour on the Democrats? No. Independents dislike both parties but by about the same amount. So the answer lies within the Democratic base. Democrats have much lower net favorability of their own party than Republicans do have for their party.

Republican net approval for their party has been as high as +80 points and remains above +60 points all year. And their disdain for Democrats is strong, consistently a net -80 points or lower.

Democrats return the favor by giving Republicans net negative ratings of close to -90 points. But when it comes to their own party, Democrats give a net favorably rating of just about +30 points, or about 30 points worse than Republicans give their party. This is who is pulling down Democratic party ratings. It is coming from inside the house.

The exception is November, when Democrat’s net favorability toward their party rose not quite 25 points, falling only a little short of Republican favorability of the GOP. But it was short lived. The shutdown ended and Democrats who were buoyed by their party’s shutdown stand, once more settled into discontent.

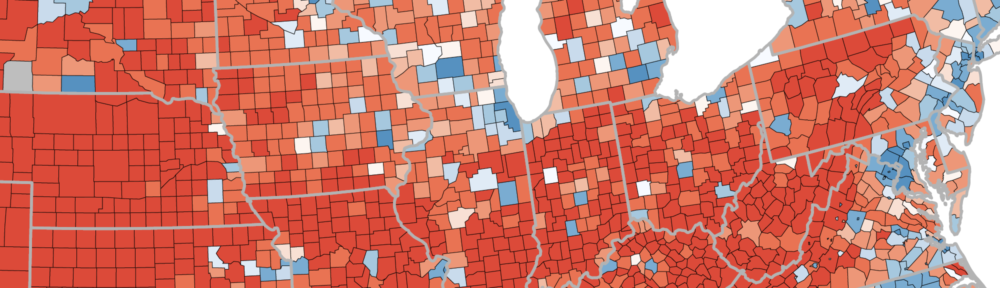

A party with weak ratings from its own base voters would not expect promising electoral outcomes. One partisan group is relatively pleased with their party’s performance, the other relatively displeased. Seems like a bad omen, yes? No. The actual performance of Democratic candidates has been quite strong for a year, with a number of seat pickups and general over-performance of 2024 margins even in losses. What gives?

Democratic partisans are, indeed, disappointed with their party, while Republicans are not. But disappointment is not producing defection. The same Democrats who are unfavorable to their party are nearly unanimous in their dislike of Donald Trump. Here is Trump favorability by party ID. Within each panel the green line is people with a favorable view of the Democratic party while the purple line is those with an unfavorable view. In the right-most panel we see that among Democrats the profound dislike of Trump is virtually identical no matter how one feels about the Democratic party. Less than 10% feel favorable to Trump.

On the Republican side, those who dislike the Democrats give Trump favorability ratings in the high 80s. The small number of Republicans who are favorable to the Democrats (this is just 6% of all Republicans), however, have shown a steady loss of affection for Trump, sinking to under 50% favorable in January. This shows that there can be defection within a party, and ironically it comes in the GOP where support for Trump is often said to be unshakable. Not to make to much of this. It is only 6% of Republicans with a liking for the Democratic party– hardly a collapse within the party. But the contrast with the Democrats is striking. Some 35% of Democrats have an unfavorable view of their party, but virtually none of them are defecting and saying they like Trump.

How about looking to November’s midterm election? My Marquette Law School Poll has asked the generic ballot question only twice so far, in November and January. Here are those results.

Net support for the Democratic congressional candidate among Democrats is nearly identical regardless of how Democratic partisans feel about their party, with a net vote in the high 80s or low 90s in both November and January. Party disaffection doesn’t matter.

For Republicans though, disaffection does matter. Among contented Republicans who dislike the Democratic party, net loyalty is also around 90 points, a mirror image of Democrats. But in that sliver of 6% of Republicans who are favorable to the Democratic party, substantial vote support goes to the Democratic candidate, at least on the hypothetical generic ballot. That defection seems to have jumped in January, but caution is in order—this 6% of Republicans is a very small sample and the January movement could just be noise.

Independents give a somewhat firmer foundation. Those independents who are favorable to the Democratic party give Democratic candidates a substantial vote margin. But even those independents unfavorable to the Democratic party produce a net margin in favor of the Democratic candidate.

Lots of people, including me, have pointed to the poor favorability rating of the Democratic party relative to the Republican party this year but haven’t tried to explain how the more unpopular party can be outperforming their rival in elections. I think the solution is here. Democrats are disappointed with their party’s performance in Congress. If we switch from favorability to approval of how each congressional party is handling it’s job we get results virtually identical to these. Disappointment doesn’t produce defection because Democrats are united in their abhorrence of the Trump administration and the GOP. The disappointment comes from the inability of the congressional Democrats to do anything. That’s why the shutdown produced a brief embrace of the party. But when the congressional Democrats settled for an end to the shutdown, with little to show for it, disaffection returned.

So far the Democratic base is unified by the negative: they are deeply against Trump and the GOP Congress. They are joined by a majority of independents who also are supporting Democratic candidates, even if they dislike each party about equally.

So long as disappointment doesn’t produce defection, Democrats can win even if they are unusually grumpy about their party.