Hmmmm. I wonder what this is about? (OK: tl;dr it is about midterm elections and what to expect in 2022).

“Surge and decline” is the title of a 1960 article by Angus Campbell:

Abstract

The tides of party voting are as fascinating as the fluctuations of economic activity. Regularities in the ebb and flow of voting with the alternation of Congressional and Presidential elections challenge the analyst to find an explanation. This article seeks it in propositions rooted in survey data.

Campbell’s explanation was that presidential elections are largely driven by “short term forces” that provide a temporary advantage to one party, usually the winner of the presidency. Then in the midterm, with no presidential election, short term forces are less important and the electorate shrinks with lower turnout (a “low stimulus election” relative to presidential) and the “long-term force” of partisanship becomes relatively more dominant in the midterm. The result is a return to the partisan balance after the surge favoring the presidential winner two years earlier.

This is a beautifully elegant theory. It is rooted in a simple model of partisanship, short-term forces and the inevitable decline of turnout in midterms. I love it.

Alas, it no longer commands general acceptance as a theory of midterm seat loss. More emphasis is now given to presidential approval, economic conditions and incumbency. Those theories bring substantial empirical evidence, and are certainly sensible. But to me they lack Campbell’s beautiful simplicity.

I’m not here to argue theories of midterm loss, but rather to simply illustrate the votes side of midterm losses. That the president’s party almost always loses house seats in midterms is a fact. Here I look at the decline in votes for the president’s party from presidential to midterm.

For fun, I’m going to walk you through the puzzle and steps that end with the figure at the top of this post. Here is the first step. What IS this??

As my poor former students know, I enjoy starting a class example with a mystery. Show the chart above, invite speculation as to what it might be. I love this one because it looks like random noise with no relationship at all.

Next step: Revealing the variables.

OK here are the variables. National Democratic percentage of the 2-party House vote in the midterm by the national 2 party vote in the previous presidential election. Not much of a relationship. Some votes go up (above the diagonal) and about as many go down (below diagonal.)

Ahh, but what about control of the presidency? The midterm-loss of seats by the president’s party is well known. The national vote, here, shows the same pattern. Dems do better (above diagonal) with GOP president, and do worse with a Dem president, almost always (except 2002.)

This is the surge and decline of votes. Almost always the president’s party wins a smaller share of votes in the midterm than they did in the presidential year. Not surprisingly, fewer votes translate into fewer seats, but that’s not our topic here. For that see this post.

The pattern is clear if we fit a regression for midterms with Rep presidents (red line) and one for Dem pres (blue line). Now the upward slope is clear (midterm performance IS related to prior pres vote) and the party of president shifts the lines up (Rep pres) or down (Dem pres).

FWIW the red and blue lines are nearly parallel. A test of a pooled model finds the difference in slopes to be statistically insignificant (p=.9465). I’m using the separate regressions here, but there would be minimal difference for a pooled model.

So what does the model tell us about, say 2018? The red line estimates the Dem 2-pty vote in 2018 to be 53.1%, up from the Dem 2-pty 2016 vote of 49.5%. In fact, Dems got 54.4%, 1.3 points better than the model and 4.9 points over their 2016 performance.

We don’t know how Dems will do in 2022, but we do know how they did in 2020 and that there is a Dem president. The vertical black line shows the actual Dem share of 2020 House vote, and the blue arrow shows the fit: a predicted 47.8% in 2022, down from 51.6% in 2020.

This is the dilemma of every presidential party: they are almost certain to lose votes in midterm elections. For closely divided congresses (looking at you 117th) this imperils majorities. 2002 was an exception, with 1998 and 1990 almost being exceptions.

How do votes translate into seats? The relationship shifted after 1994 undoing a long standing Dem advantage. The votes-to-seats model expected Dems to hold 50.6% or 220 seats in 2021 (actual post-election was 222). For 2022 the estimate is 45.0% of seats. That would be 196 seats, a loss of 26 from the post-2020 election total.

The president’s party gained house seats in 1934, 1998 and 2002, and lost share of seats in every other midterm since 1862. Reps gained seats in 1902 as the House expanded but actually lost share of seats as Dems gained more that year.

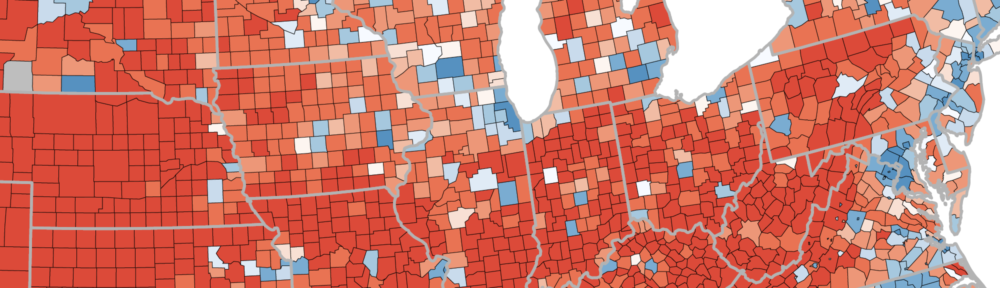

If the historical pattern applies in 2022 the Democrats are unlikely to hold control of the House. In addition there will also be the effect of redistricting. Both parties will have an incentive to gerrymander for every advantage possible where they control the process.

Of course the past pattern may change. Political skill or folly might shift the balance away from the models. The model is useful because it gives us a basis for our expectations. We can judge party performance by whether outcomes exceed or fall short of model expectations. 12/12