A question from @Rufus_GB about the validity of issue polling is linked below.

Here is more of an answer than may have been wished for, largely via links to more thorough analysis than Tweets provide.

I question the value of issue polling, in general, because the results can vary so wildly based on the wording of the question. On Roe, it’s that issue plus the fact that I don’t believe many (most?) Americans understand what Roe actually does/doesn’t do. Thoughts?— Rufus (@Rufus_GB) December 7, 2021

On abortion, wording matters but don’t confound wording with substantively different aspects of the issue. If we ask about “for any reason” or about “serious defect” that is not just wording but different circumstances. Decades of work show the circumstances matter a lot.

See this review of abortion polling since 1972 by @pbump in @washingtonpost

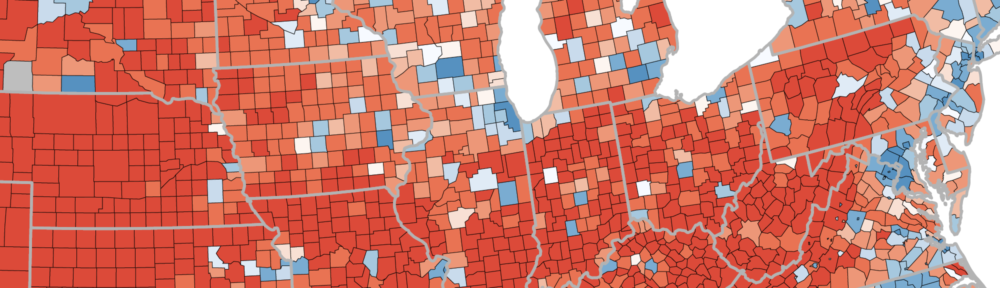

The GSS has asked same questions since then, with 7 different circumstances. There are clear consistent differences. That is much more revealing than just “wording”. From @pbump article:

In my @MULawPoll Supreme Court surveys in Sept. & Nov. 71% of those with an opinion oppose striking down Roe, 29% favor striking it down. But 54% would uphold the 15 week ban in Dobbs, 46% oppose, again of those w an opinion.

Those are substantive differences and make sense.

Here is my analysis of that, including a look at who doesn’t have opinions on the abortion questions. Not all do, and that is also important for understanding issue polls.

The fact that people respond to issue polls differently when the questions raise different aspects of an issue seems an obvious strength of issue polling– circumstances matter, and respondents are sensitive to those circumstances.

If people responded the same way regardless of the circumstances presented in the question, we’d suspect they weren’t paying attention!

There has been a number of recent articles claiming that issue polls are “folly” or that they have seriously missed on state referenda. (And they have missed on some referenda, but the big misses are highlighted and better performance is ignored.)

The Sweep: The Folly of Issue Polling

There are important criticisms: public awareness of issues & information about the issues may be limited. Folks will give an answer but it may not mean much to them. Politicians don’t just “do what the majority wants” so policy doesn’t follow the polls very closely or quickly.

Some might say policy doesn’t mirror opinion polls, and blame polls. I’d think the elected officials might share the blame. They do respond to public opinion sometimes, but they are also responsive to interest groups and donors issue preferences. If they don’t adopt policy in line with public majorities, I’d look at those other influences for part of the story,

Issue polls often don’t have an objective “right answer.” That is what elections do for horse race polls: we know the final answer. But there isn’t a “true” measure of presidential approval or support for an issue. So how do we know?

Referenda provide a chance to measure issues

The most comprehensive analysis of referenda voting and polls was presented at AAPOR in May 2021 by @jon_m_rob @cwarshaw and @johnmsides

60 years of referenda and polling and accuracy and errros, w/o cherry picking.

The fit of outcomes to polls is pretty good, but there are also some systematic errors: more popular issues underperform on referenda, and more unpopular ones overperform, doing better than expected.

The fit varies across issues, but the relationship of polls to outcomes are positive in almost all issues.

Read the full set of slides. They highlight some of the criticism but provide the most comprehensive analysis of issue polls when we have an objective standard for accuracy. The results are pretty encouraging for issue polling’s relevance.

Issue polling may be criticized but those with policy interests use them. In the absence of public issue polls, the interest groups would know what they show but the public wouldn’t. That seems a good reason to have public issue polling.

There are plenty of examples. Here is one from the right, from HeritageAction.

Pew did a careful look at how much issue polls might be affected by the type of errors we see in election (horserace) polls. Probably not by very much.

Fivethirtyeight.com also looked at issue polls: Their analysis is here.

An election poll off by 6 points is a big miss & we saw a number of those in 2016 & 2020. But issues are not horseraces. If an issue poll shows a 6 point difference between pro- and anti-sides, 53-47, we’d characterize that as “closely divided opinion.” If it shows 66% in favor to 34% against, a 6 point error wouldn’t matter much. The balance of opinion would be clear regardless. Also, issue preference is not the same as intensity so good issue polling analysis needs to look at whether the issue has a demonstrable impact on other things like vote, or turnout, or if the issue dominates all others for some respondents. Plenty of issues have big majorities by low intensity or impact.

There are good reasons to be careful about interpreting issue polls. But the outright rejection of them is not grounded in empirical research. I suspect it is to deny that “my side” is ever in the minority. It is especially in the interest of interest groups to dismiss them, even as they rely on them.