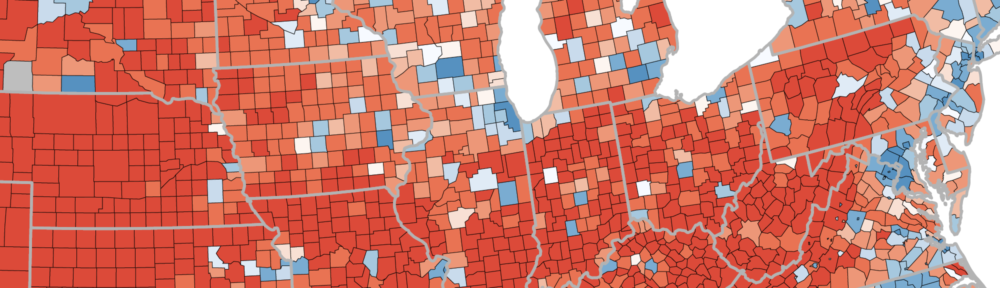

Wisconsin Votes 2024, an abstract view

Here is a simple guide to the county votes for president and Senate in Wisconsin on November 5, 2024.

Donald Trump won 59 Wisconsin counties while Kamala Harris won 13.

Where does the vote come from and how much? The Democratic net vote comes with huge margins in Dane and Milwaukee counties, followed by much smaller margins in 11 other counties. The large Republican margins come from Waukesha and Washington. The many smaller Republican leaning counties collectively provide Republican strength, offsetting the fewer counties with Democratic majorities, despite the large margins in Dane and Milwaukee.

Harris improved over Biden’s 2020 vote percentage margin in only four counties, Washington, Ozaukee, Waukesha (the legendary Republican WOW counties around Milwaukee) and Door. She did a bit worse than Biden in Eau Claire, Dane and (especially) La Crosse, usually Democratic strong holds.

Baldwin won 14 counties, including Sauk which Trump won, while Hovde won 58.

While Baldwin only narrowly out-performed Harris, winning by .9 percentage points while Harris lost by .9 percentage points, Baldwin outperformed the presidential ticket in all but four counties: Menominee, Ozaukee, Waukesha and Washington.

A year ago there seemed to be a serious threat to Trump in the GOP. His name was DeSantis.

In March 2023, DeSantis won 35% to Trump’s 40% of GOP registered voters. (Haley was at 5%)

But DeSantis only lost ground through the year, while Trump gained.

Still, Trump didn’t move much past 50% until after Jan. 2024 once the primary process began.

As of Feb 5-15, 2024, pre-South Carolina primary, Trump holds 73% nationally to Haley’s 15% and DeSantis is no longer a candidate.

Trump rose modestly in the spring, then more in the fall, with a big jump by February. Haley was slow to rise, then bumped up in Nov. and Feb., but to only 15%.

The race that could have been.

DeSantis not only started strong but was a threat to Trump from within the Trump wing of the party. In March 2023 DeSantis got 32% among Reps *favorable* to Trump, plus 45% among those unfavorable to Trump.

Had DeSantis been able to expand that incursion into Trump land this could have been a real race. He did not. Instead DeSantis’s support fell across both Trump-favorable and Trump-unfavorable Republicans. Whether because of Trump’s effective attacks on DeSantis or the failures of DeSantis, the race that could have been was not.

Nikki Haley instead is the last contender standing against Trump, and yet she fails to reach even 20% support. She never was a contender with those who like Trump, not reaching even 6% among the Trump-favorable Republicans. But she has captured the wing of the GOP that does not like Trump, winning 65% of those Republicans.

For her, the tragedy is that nothing in the campaign succeeded in increasing the share of those unfavorable to Trump. Instead the opposite occurred, Trump’s favorability hovered around 70% until July, then rose to 80% in Sept. and stands at 84% in February.

As Haley has won an increasing share, now 2/3rds, of Republicans unfavorable to Trump, that pool has declined by half, from 30% to 16%. Even taking all of this smaller pool cannot make an alternative to Trump competitive in the primaries.

A year ago, 30% of Republicans were unfavorable to Trump, and DeSantis was eating into Trump-favorable Republicans. His effort failed. Haley has never won more than negligible support from the Trump-favorables, and even as she has consolidated the support of Trump-unfavorable Republicans, that group has been shrinking, to now less than one in five Republicans.

In March 2023 the GOP had a significant 30% who did not like Trump and a majority who supported someone else or were undecided. That moment has passed.

Debates are followed by “instant reaction” polls of debate viewers, taken overnight and posted the day after. These have some value in capturing opinion of those so interested they actually watched the debate. But this is a poor measure of the impact of the debate, which to be meaningful neeeds to be lasting. Debate performance is as much, or more, about launching the next month for the campaign as it is about the snappy line of the moment.

Thus there is more than the usual need for a slow polling look at the debate. Now, nearly a month after, do we see any meaningful shift in candidate standing with voters? And was the response steady over time, or a blip that quickly faded? On the eve of the second debate, let’s get a clear view of the impact of the first debate.

A month before vs. a month after

I look at the polls taken in the month (26 days) following the debate, Aug. 24 through Sept. 18 (the most recent poll as of Sept 21), and compare polls taken in the 28 days prior to the debate (July 25-Aug. 22). Let’s call these the “pre-” and “post-debate” polls.

First, how do the candidates stand in national polls of Republicans and independents who lean Republican registered voters? Data are from the FiveThirtyEight.com collection of national polls.

Figure 1 shows the comparison for the eight debate participants. Only Nikki Haley has a meaningful increase in support, up 2.4 percentage points following the debate. No one else changes by even a single percentage point.

The trends before and after the debate tell the same story. Haley looks to have continued to rise after the debate, while Ramaswamy has slightly declined, as has DeSantis. All these changes are small, except for Haley.

The means and medians and number of polls are shown in the table below. In contrast to Haley’s increase, Christie and Trump rise by less than a tenth of a percentage point while the rest decline, all by less than a percentage point. Pence, Scott and DeSantis have the largest declines, though even DeSantis is down by only 0.6 percentage points.

And the candidate who wasn’t there didn’t get a boost or a drop: Trump’s support changed by 0.03 percentage points.

If the debate was thought to potentially scramble the standings, it did so only for Haley, though her support remains in single digits. Pence and Ramaswamy took much of the debate time, and a good bit of post-debate commentary. Neither has seen a lasting payoff.

Quick polls get attention, but slow polls are more illuminating.

In my previous post I argued that the indictments of former president Donald Trump did not in fact boost his standing with voters, despite the often repeated claim that they did.

Two folks I respect pushed back on the NY indictment, though agreeing the others had no effect. Here I respond, and agree in part. In any case, I think this shows a positive discussion is possible over such matters! My bottom line is Trump may have gained support in the GOP primary following the NY indictment. But I don’t find evidence of any gain in overall favorability with all registered voters. My new analysis (thanks to Philip and Sam) finds some evidence that the Florida indictment lowered his support and favorability, something I did not mention in my original post..

Since my original post, Philip Bump at The Washington Post published a nice story looking at my claim, and concluding there was in fact a boost from the first indictment in New York but agreeing there were no boosts from the subsequent indictments. See his piece here. (Link should not be paywalled.)

Sam Wang posted a similar point on Bluesky (sorry, don’t know how to copy a link to that)

Let’s start with the strong case, a rise in Trump GOP primary support following the NY indictment. Here is Trump’s percentage i.n GOP primary polls before and after each indictment. (I’ve updated the most recent polls since my original post, which affects only the post-GA data.)

We all agree the post-New York support is higher than pre-indictment. The only disagreement is that there was a trend of rising Trump primary support before the indictment and that rise continued for over a month after the indictment. My original post claimed the post-NY increase was primary due to the pre-existing trend, rather than an indictment effect. Bump and Wang disagree and see an indictment effect. Here is the chart with the full trend.

The red line shows the overall trend across all polls, the dots are individual polls. The high-frequency polls from YouGov (85 in all) make up the dense set of dots mostly above the red trend line. Those dense dots DO show a bump up immediately after the NY indictment. In my original post I discounted that, thinking the red line was increasing before and after and I gave more weight to that. But I discounted the dense set of polls that do rise. Wang raises the point but Bump dives into this and does more substantial analysis that I now think supports a NY indictment effect.

Here are my finding on this, in response to their points, and finding myself now agreeing there was an independent effect of the NY indictment even considering the trend before and after.

I fit several models, but here are the two that make me conclude NY had an effect. The dependent variable is Trump percent in primary polls. You do NOT want to use his margin over DeSantis because the latter has been declining steadily, so the margin confounds Trump support with DeSantis’ weakening. As you can see in the chart, Trump has been pretty flat since mid-May.

The models I fit are a polynomial in time, which allows for the curve of the support trend, which rises, then flattens. Obviously not a constant linear trend. I fit one quadratic and one cubic fit (the latter probably overfitting the trend but our focus in on the coefficients for the indictments.)

The first model is the quadratic trend.

The NY coefficient is a 4.12 percentage point increase in Trump support after the indictment, and is a statistically significant effect. So this agrees with Bump and Wang, and shows I dismissed this effect too quickly.

The model also suggests that the Florida indictment may have lowered Trump’s support by 2.8 points, a marginally statistically significant result. There is no evidence that DC or GA indictments changed his support. Both have negative but non-significant estimates.

An issue is whether the quadratic trend is sufficient to capture the trend over time, independent of the indictments. As a check I reestimate the model with a cubic in time. That model is shown next.

The NY effect here is a 4.8 point increase, which remains statistically significant. The Florida effect remains negative but falls short of statistical significance. So either way, the NY indictment seems to have boosted Trump with GOP primary voters over and above the trend leading up to the indictment.

On the other hand, Trump’s favorability ratings with all registered voters don’t seem to have gone up with NY, but may have declined slightly with the FL indictment.

Here the trend is nearly flat since January, so I estimate one model that is linear in time, and one that is quadratic as a robustness check. The linear time model is

The time trend is virtually flat, with no evidence of a NY indictment effect. However, the Florida indictment seems to have lowered favorability by 3.6 points.

Using a quadratic in time is similar:

The Florida estimate is a 3.8 point decrease in favorability, and marginally significant, with no evidence for a more complicated time trend. As a final check I ran a cubic time trend with the FL coefficient of -3.5, but p=.056 so not as convincing an effect.

Bottom line is the NY indictment didn’t show any evidence of boosting Trump’s favorability among all registered voters, but it does seem to have improved his standing in the GOP primary by 4.1 to 4.8 points depending on the model.

My thanks to Philip and Sam for pushing this point and adding to the analysis.

To cut to the chase, the indictments of Donald Trump have not boosted him in the polls, either for favorability or for his support in the GOP primary. This claim keeps being repeated as if the data support it. It does not.

Net favorability nationally

Trump’s net favorability (percent favorable minus percent unfavorable) inched up 1.5-2 points following the first indictment in New York on March 30, 2023, from a median of -14.0 to -12.5, and mean of -14.2 to -12.2. This is the only period of a (slight) improvement compared to the pre-indictment period (Jan. 1 to Mar. 29), Following the Florida indictment the median fell to -18, then -19 after the DC indictment and rose -17.5 after Georgia. (Table of full results below.)

The net favorability is for the national population, so perhaps Trump gained substantially among Republican voters, but not the full population. His support in the GOP primary vote gives us that test.

Trump GOP Primary support

Compared to pre-indictment, Trump did have higher support among Republicans in the primary vote following the New York indictment, a median of 49% prior to the NY indictment and 57% after NY but before Florida. There was no further change after Florida (still 57%), or after DC (still 57%.) After the Georgia indictment the median is 58%. If there was in indictment effect boost at all (see below for why you should doubt that) it was over by the Florida documents case indictment.

The remaining doubt about indictment effects is provided by the trend chart below. Trump’s support for the nomination had been rising steadily since Jan. 1 through the spring. It rose at the same rate following the New York indictment as it had been rising prior to the indictment. The trend levels off in early May, a month after the NY indictment and about a month before the Florida indictment. Since mid-may there has been very little trend in Trump’s primary vote. (Each point in the chart is a national poll and the red line is a local regression trend estimate.) Trump’s margin over DeSantis has continued to climb but that is due entirely to DeSantis’ collapse in the polls, not to any gains by Trump since May. Trump’s current 58% support is more than enough to win the nomination. But it hasn’t been increasing for four months.

There are reports of surges in donations following the indictments. But if so, that hasn’t been reflected in the polling for either favorability or for GOP primary support.

The table below shows the median, mean and number of national polls used in the charts above. Note there are only 4 favorability polls completed between the DC and GA indictments, though there were 16 primary polls in the same interval.

“Indictments help Trump” is folklore that needs to be corrected. There is no polling evidence the indictments help, or hurt, Trump. Any effect of criminal trials remains to be seen.

Reference

The October 2022 term (OT2022) of the U.S. Supreme Court produced elements of a 3-3-3 division, with three reliable liberal justices, a Roberts-Kavanaugh-Barrett coalition and a slightly less cohesive conservative group of Gorsuch-Thomas-Alito.

Analysis here is based on the rates of agreement in judgment presented by EmpiricalSCOTUS. Their work is much appreciated.

Figure 1 shows the non-metric spatial scaling of the justices in two dimensions. The horizontal x-axis shows a clear left-right ordering of the justices based on their agreement in judgment.

Note that the left-right dimension reflects relative location, not an absolute measure of ideology. The three justices near zero are “in the middle” but that does not mean their positions are “moderate” in some objective sense. Further, the detailed content of opinions is not reflected by these agreement measures, which only tell us the voting coalitions, not the legal consequences of the rulings.

By this measure, Kagen, Sotomayor and Jackson are closely packed on the left of the Court. Roberts, Kavanaugh and Barett cluster in the middle, with Roberts slightly less conservative and Barrett slightly more conservative than Kavanaugh. On the right, Gorsuch is less to the right than Thomas, with Alito anchoring the right end of the Court.

The vertical, y-axis, dimension does not fit the notion of an “institutionalist” dimension that seemed to appear in 2021. Vertically, Jackson and Gorsuch are similar, as are Sotomayor and Alito, Kagan and Roberts, and Barrett and Thomas, with Kavanaugh in the middle of all. Without giving a label to this dimension, it is notable that the three most conservative justices are more spread out across this 2nd dimension than the three liberals or the three middle justices. In this we see a reflection of the lower agreement among Gorsuch, Thomas and Alito than among either of the other two clusters.

Figure 2 shows the agreement among justice as a heat map. The ordering here (which combines both dimensions) is slightly different than the left-right order in Figure 1, though the groupings are the same. Light shades indicate stronger agreement and dark shades indicate greater disagreement between each pair of justices.

The branches in the left and top margins show which clusters form in order of internal similarity and external difference. The first branch is clearly the 3 liberals vs the 6 conservatives. Next is the distinction between the 3 middle justices and the 3 most conservative ones. There are then finer, and more modest, distinctions within each of the 3 clusters, splitting Kagan, Barrett and Thomas slightly away from the other two justices in their clusters.

The grouping in OT2022 clearly argues for two primary clusters (the 3-6 Court) and for three secondary clusters (the 3-3-3 Court).

The similarly light shading of the Kagan-Sotomayor-Jackson group and the Barrett-Kavanaugh-Roberts group shows these two clusters were similar in high inter-agreement within the group. The three most conservative justices cluster in a somewhat less cohesive group, compared to the other two groupings. This reflects their relative disagreement on the 2nd dimention in Figure 1.

The table of agreement in judgement measure is shown in Table 1, with the three clusters highlighted.

Agreement among the three liberal justices range from 89%-95%, and among the three center justices also ranges from 89%-95%. In the cluster of the most conservative justices agreement is a bit lower, from 76%-87%. This less cohesive group is reflected in the spread in the 2nd dimension in Figure 1.

The liberal cluster has remained well defined with the addition of Jackson replacing Breyer in OT2022. In OT2021, Roberts and Kavanaugh agreed 100% of the time, defining the middle but not closely joined by Barrett who was more often aligned with the right cluster in both OT2020 and OT2021.

Using Republicans and independents who lean Republicans, Trump gets 31% and DeSantis gets 30%, a surprisingly close race. Trump leads by considerably more in other states and in national polls. What’s going on in my June Wisconsin @MULawPoll?

One might ask if independents who lean Republican are distorting this. But no. Among “pure” Republicans, Trump gets 35% and DeSantis gets 34%. Among independents who lean Republican, there are more other and undecided choices but the margin is not much changed: Trump gets 23% and DeSantis 25%.

So the close first choice race is not because of including leaners: it is a 1 point Trump margin without leaners too. (Scroll right for full table)

| Group | Chris Christie | Ron DeSantis | Larry Elder | Nikki Haley | Asa Hutchinson | Mike Pence | Vivek Ramaswamy | Tim Scott | Donald Trump | Haven’t decided |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Rep+Leaners | 1 | 30 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 6 | 3 | 5 | 31 | 21 |

| Rep | 1 | 34 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 35 | 18 |

| Lean Rep | 1 | 25 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 7 | 4 | 6 | 23 | 27 |

DeSantis picks up a big margin in the head-to-head second choice question, DeSantis 57% to 41% for Trump. Who moves from the first choice?

Those who pick another named Republican candidate (other than DeSantis or Trump) break 74-25 for DeSantis on the 2nd choice. And the undecided on first choice break 65-28 for DeSantis. See Table 2.

Trump is a lot of Republican’s first choice, but barely a quarter switch to him as their 2nd choice.

| 1st choice | Donald Trump | Ron DeSantis | Don’t know |

|---|---|---|---|

| DeSantis | 1 | 98 | 1 |

| Trump | 98 | 2 | 0 |

| Other candidates | 25 | 74 | 1 |

| Undecided | 28 | 65 | 7 |

Despite getting just 31% of first choice votes, Wisconsin Republicans still like Trump. Of all Reps and leaners, Trump favorability is 68% and unfavorable is 30% with a tiny 2% who say they haven’t heard enough about him.

Favorability is a shade higher with pure Reps, 72%, and a good bit lower, though still net positive at 60%, among leaners. Those ratings are shown in Table 3 (a). In October 2022, Trump was 78% favorable among Reps and 62% favorable among leaners, so a little decline with both, but not massive change.

DeSantis favorabiity is shown in Table 3 (b). He is 1 point behind Trump overall, 2 points above Trump on favorable with pure Republicans, and 7 points below Trump among leaners, but with much more haven’t heard enough and less unfavorable.

So there may be a small recent decline in Trump’s favorable ratings with Reps and with leaners, it isn’t a lot compared to where he was in October 2022.

Table 3: Favorability by Rep and Lean Rep Party ID

| Group | Favorable | Unfavorable | Haven’t heard enough |

|---|---|---|---|

| All Rep+Leaners | 68 | 30 | 2 |

| Rep | 72 | 25 | 3 |

| Lean Rep | 60 | 39 | 0 |

| Group | Favorable | Unfavorable | Haven’t heard enough |

|---|---|---|---|

| All Rep+Leaners | 67 | 14 | 20 |

| Rep | 74 | 10 | 16 |

| Lean Rep | 53 | 21 | 26 |

Maybe these are somehow less Trump supportive Reps than they should be.

Asked to recall their vote in 2020, 95% of Reps say they voted for Trump, as do 79% of the leaners. In our late October 2020 poll, 90% of Reps and 79% of leaners said they were voting for Trump. This is not a peculiarly anti-Trump sample of Republicans.

Table 4: 2020 vote recall by party id, and Oct. 2020 pre-election vote

| Group | Donald Trump | Joe Biden | Someone else |

|---|---|---|---|

| All Rep+Leaners | 90 | 5 | 5 |

| Rep | 95 | 4 | 1 |

| Lean Rep | 79 | 7 | 13 |

| Group | Donald Trump | Joe Biden | Jo Jorgensen |

|---|---|---|---|

| All Rep+Leaners | 86 | 7 | 3 |

| Rep | 90 | 6 | 1 |

| Lean Rep | 79 | 8 | 6 |

There is a clear long term change in GOP views of Trump in Wisconsin since 2020. While he retains a core of vigorous supporters, Republicans and leaners do not have as favorable a view of Trump as they did in 2020. Table 5 shows this trend since January of 2020 until June of 2023.

| Poll dates | Favorable | Unfavorable | Haven’t heard enough | Don’t know |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1/8-12/20 | 83 | 16 | 0 | 1 |

| 2/19-23/20 | 87 | 10 | 1 | 1 |

| 3/24-29/20 | 84 | 12 | 0 | 3 |

| 5/3-7/20 | 88 | 9 | 1 | 1 |

| 6/14-18/20 | 81 | 13 | 3 | 3 |

| 8/4-9/20 | 83 | 14 | 1 | 2 |

| 8/30-9/3/20 | 80 | 15 | 3 | 1 |

| 9/30-10/4/20 | 85 | 13 | 2 | 1 |

| 10/21-25/20 | 88 | 11 | 1 | 0 |

| 8/3-8/21 | 75 | 18 | 3 | 3 |

| 10/26-31/21 | 72 | 23 | 2 | 4 |

| 2/22-27/22 | 70 | 21 | 3 | 5 |

| 4/19-24/22 | 68 | 24 | 3 | 4 |

| 6/14-20/22 | 75 | 19 | 3 | 3 |

| 8/10-15/22 | 71 | 21 | 2 | 5 |

| 9/6-11/22 | 72 | 24 | 0 | 4 |

| 10/3-9/22 | 70 | 22 | 2 | 6 |

| 10/24-11/1/22 | 72 | 17 | 2 | 6 |

| 6/8-13/23 | 68 | 30 | 2 | 1 |

For completeness, Table 6 shows the trends for pure Republicans and for leaners.

Table 6: Trump favorability, Jan. 2020-June 2023, among Replicans and leaners separately

| Poll dates | Favorable | Unfavorable | Haven’t heard enough | Don’t know |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1/8-12/20 | 87 | 12 | 0 | 0 |

| 2/19-23/20 | 91 | 7 | 1 | 1 |

| 3/24-29/20 | 88 | 10 | 1 | 2 |

| 5/3-7/20 | 92 | 5 | 1 | 1 |

| 6/14-18/20 | 84 | 12 | 1 | 4 |

| 8/4-9/20 | 85 | 13 | 1 | 1 |

| 8/30-9/3/20 | 84 | 11 | 3 | 1 |

| 9/30-10/4/20 | 90 | 9 | 1 | 0 |

| 10/21-25/20 | 89 | 10 | 1 | 0 |

| 8/3-8/21 | 83 | 12 | 3 | 2 |

| 10/26-31/21 | 77 | 18 | 2 | 2 |

| 2/22-27/22 | 80 | 11 | 2 | 5 |

| 4/19-24/22 | 73 | 19 | 2 | 4 |

| 6/14-20/22 | 81 | 17 | 1 | 0 |

| 8/10-15/22 | 77 | 15 | 2 | 5 |

| 9/6-11/22 | 79 | 16 | 0 | 4 |

| 10/3-9/22 | 78 | 15 | 2 | 5 |

| 10/24-11/1/22 | 78 | 12 | 3 | 5 |

| 6/8-13/23 | 72 | 25 | 3 | 0 |

| Poll dates | Favorable | Unfavorable | Haven’t heard enough | Don’t know |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1/8-12/20 | 76 | 22 | 1 | 1 |

| 2/19-23/20 | 78 | 18 | 1 | 3 |

| 3/24-29/20 | 78 | 17 | 0 | 5 |

| 5/3-7/20 | 81 | 16 | 1 | 1 |

| 6/14-18/20 | 76 | 17 | 6 | 1 |

| 8/4-9/20 | 78 | 16 | 2 | 3 |

| 8/30-9/3/20 | 73 | 25 | 2 | 0 |

| 9/30-10/4/20 | 74 | 19 | 5 | 2 |

| 10/21-25/20 | 84 | 14 | 1 | 0 |

| 8/3-8/21 | 60 | 30 | 4 | 5 |

| 10/26-31/21 | 60 | 31 | 2 | 6 |

| 2/22-27/22 | 53 | 37 | 5 | 4 |

| 4/19-24/22 | 58 | 35 | 4 | 2 |

| 6/14-20/22 | 62 | 23 | 7 | 8 |

| 8/10-15/22 | 61 | 33 | 1 | 6 |

| 9/6-11/22 | 57 | 39 | 0 | 4 |

| 10/3-9/22 | 54 | 35 | 2 | 7 |

| 10/24-11/1/22 | 62 | 26 | 1 | 8 |

| 6/8-13/23 | 60 | 39 | 0 | 1 |

Our GOP respondents aren’t as into Trump as in the past, but crossing over to vote for Biden remains a bridge too far. That goes for both Trump and DeSantis when matched against Biden, though DeSantis does a bit better with leaners, in Table 7.

Table 7: 2024 vote by party strength

| Party stength | Donald Trump | Joe Biden | Haven’t decided | Don’t know | Refused |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rep | 93 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Lean Rep | 78 | 12 | 6 | 1 | 3 |

| Party stength | Ron DeSantis | Joe Biden | Haven’t decided | Don’t know | Refused |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rep | 94 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Lean Rep | 87 | 12 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

Wisconsin Republicans are less attached to Trump than in 2020, are considering alternatives or are undecided, but not quick to embrace Trump if he isn’t already their 1st choice. But for the general election, they remain strongly Republican regardless of the candidates, and quite unwilling to vote for Biden.

It is “big decisions” week at the U.S. Supreme Court. While most people have an opinion about how the Court is handling its job, the details are often obscure to a substantial share of the public. This week’s decisions will come as surprises to many who don’t follow the Court’s docket.

The Court has suffered a substantial decline in approval since 2020, when fully 66% approved of the job the Court was doing. As of May, 2023, approval stands at 41%. All the data reported here is from the Marquette Law School Poll national surveys of adults.

Approval of the Court differs sharply by party identification, with Republicans maintaining a high approval rating around 60% but independents dropping into the 30s and Democrats into the 20s.

There has been considerable stability in views of the Dobbs decision, which struck down Roe v Wade in June 2022, at least among those who have an opinion on the case (more on those without an opinion below.) About 2/3rds oppose overturning Roe, while 1/3rd support the Dobbs decision.

Approval has changed in “sensible” directions, following party and shifting as the Court has issued major decisions. Disagreement with outcomes drives approval down, agreement with outcomes increases approval. Few of the public are aware of the details of legal reasoning in decision, though elite discourse may emphasize textualism or originalism or “history, text, and tradition” based arguments.

The limits of public attention to the Court is vividly illustrated by awareness of the balance of justices nominated by Republican and by Democratic presidents. Nominations have been intensely contested for over a decade (arguably longer) and the three Trump appointments followed in the wake of Obama’s nominee being denied hearings or a vote in 2016 following Justice Scalia’s death. If a lot of politics has been “all about the judges”, much of the public hasn’t followed the story.

Despite a long standing Republican-appointed majority on the Court, and the current 6-3 majority, 30% of the public believes a majority of the justices were appointed by Democratic presidents. About 40% say a majority was “probably” appointed by Republican presidents, and just 30% say a majority was “definitely” appointed by Republican presidents.

In the wake of the Dobbs decision there was a 10 point rise in the percent saying “definitely” Republican appointed majority, and a drop of 10 points in the percent incorrectly believing Democrats had appointed a majority. But this increased information has declined over the year since Dobbs, giving up all those gains to return to where it was, with 30% saying definitely Republican majority and 30% thinking Democratic appointees are the majority.

For those following, or reporting on, the Court, the share of the public unaware of the makeup of the majority is striking. Discussion of the Court generally assumes some facts are universally known, but this is not the case.

The Dobbs decision has shifted the policy landscape after 50 years of settled law, and has made abortion a central issue in many campaigns as state legislatures have adopted sharply differing laws, replacing the basic national standards for abortion rights under Roe and Casey that had prevailed.

The Dobbs case was clearly on the horizon for months before it was decided. Yet when we (the Marquette Law School Poll) asked about it in Sept. 2021, 30% said they “haven’t heard enough to have an opinion.”

Pre-decision

Do you favor or oppose the following possible future Supreme Court decisions, or haven’t you heard enough about this to have an opinion?

Overturn Roe versus Wade, thus strike down the 1973 decision that made abortion legal in all 50 states.

Post-decision

Do you favor or oppose the following recent Supreme Court decisions, or haven’t you heard enough about this to have an opinion?

Overturned Roe versus Wade, thus striking down the 1973 decision that made abortion legal in all 50 states.

The leak of the Dobbs opinion raised awareness about 8 points while the actual decision increased awareness another 10 points. By the fall of 2022, about 10% said they hadn’t heard of the Dobbs decision. This is an example of how an extraordinarily salient decision can reach almost all of the public, certainly more than the typical case or of the Court majority above.

This week, we expect a decision on the use of race as a factor in college admissions. This issue has been with us at least since the Bakke case in 1978, and has been revisited since, notably in Grutter v. Bollinger (2003).

As of May, just over half of our national sample say they haven’t heard about the case or not enough to have an opinion.

Do you favor or oppose the following possible future Supreme Court decisions, or haven’t you heard enough about this to have an opinion?

Rule that colleges cannot use race as one of several factors in deciding which applicants to admit.

Whatever decision the Court reaches, it will come as something of a surprise to half the public. When we poll in July, it will be interesting to see how many remain unaware of this decision. Will that fall sharply, as in Dobbs, or will a substantial minority remain unaware of the decision?

A similar lack of familiarity is clear in another much talked about case (among Court watchers), 303 Creative, which concerns a business owner’s right, based on 1st Amendment speech or religious liberty grounds, to deny services to LGBTQ customers. Here too, about 45% lack awareness of the pending decision.

While a plurality favor banning the use of race in admissions, a plurality oppose allowing businesses to deny services. But in both cases the largest group is those not familiar with the case.

Views of the justices

Despite recent coverage of the justices, most of the public says they either haven’t heard of each justice, or haven’t heard enough to have a favorable or unfavorable opinion. Here we encourage respondents to say if they lack an opinion. Our question reads:

Some justices of the Supreme Court are better known than others. For each of these names have you never heard of them, heard of them but don’t know enough to have an opinion of them, have a favorable opinion or have an unfavorable opinion?

In other surveys (including ours for different questions) “haven’t heard enough” or “don’t know” may not be an explicit option. Many respondents will offer an opinion in this case. Those responses may also contain valuable information, encouraging reluctant respondents to still venture an opinion. In light of our finding on awareness of the majority on the Court, and on specific cases, we choose to frame the question in a way that explicitly acknowledges the possibility that not every justice is well known.

As the chart makes clear, many people lack opinions of each justice. There is variation, with some better known than others, but the share of “haven’t heard enough” is higher than either favorable or unfavorable for all, if only slightly so for Justice Thomas.

More than 60% say they don’t have an opinion of Justice Alito. In November 2022 we asked respondents for their best guess as to which justice authored the Dobbs decision. A quarter correctly picked Alito, with another quarter picking Thomas, and a scattering among the other justices. This is a very difficult question for the general public, who do not as a rule rush to read opinions by their favorite justices. Perhaps it is impressive that as many as 1/4 got Alito right, and Thomas is not a bad guess, given his concurrence. Still, the point is most people don’t have specific information about individual justices even in the most visible decisions.

The May 2023 survey was conducted after a series of news stories concerning Justice Thomas’ financial disclosure statements, which did not report a real estate sale or certain travel expenses paid by others. Thirty-three percent said they had heard a lot about this, while 32% had heard a little and 35% had heard nothing at all. This was a prominent story in “Washington circles” but while 1/3rd heard a lot about it, just over 1/3rd heard nothing at all.

There is a substantial difference in awareness of the Court among those who generally pay attention to politics, which is nicely illustrated by awareness of the stories about Justice Thomas’s disclosure statements. About 36% in the May survey said they paid attention to politics “most of the time” while 64% pay attention less frequently.

News stories about Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas’ financial disclosure reports. (Here are some recent topics in the news. How much have you heard or read about each of these?) By attention to politics.

| Attention to politics | Heard a lot | A little | Nothing at all |

| Most of the time | 60 | 28 | 12 |

| Less often | 18 | 34 | 48 |

In the most attentive 1/3rd of the public, awareness of the stories about Thomas’ disclosures were quite well known, but this dropped precipitously once we move beyond those most attentive to politics generally.

The lesson is an old one. Most people don’t pay as much attention to either politics or the Court as you, dear reader, or I. This means public reaction to Court decisions may not follow what elite expectations may be, simply because much of the public wasn’t expecting the cases to be decided. Even in Dobbs, a substantial 30% didn’t see the case coming as late as March 2022.

Further, given how much partisanship affects perceptions of the Court, the 25-30% who believe there is a majority appointed by Democratic presidents will have curiously distorted opinions of the court. In May, among Republicans who eroneously believed a majority of the Court were appointed by Democratic presidents, 57% disapproved of the Court. Among Democrats with the same misperception, 60% approved of the Court. Compare that with Republicans correctly saying there is definitely a Republican appointed majority: 76% approve, while among Democrats also saying there is definitely a Republican appointed majority: 14% approve.

There is a reporting and messaging lesson here. A substantial share of the audience you are trying to reach is likely unaware of some facts you take for granted. It is important to expand awareness of those facts by making them part of your story, even if they seem “obvious.”

Which GOP candidates pose a threat to Donald Trump among Republican voters?

In May Trump had 72% favorable and 26% unfavorable (2% didn’t have an opinion of him) among registered Republicans and independents who lean Republican in the Marquette Law School national poll. That high favorability rating is Trump’s great strength in the party. His favorability has been consistently high, though it declined a bit in the fall of 2022 then turned back up in May.

The other GOP candidates are less well known than Trump, even Pence and DeSantis lack the universal recognition of Trump. But low name recognition at this point can be an opportunity for those less well known to introduce themselves to many voters for the first time. Only Christie, Hutchinson and Sununu (who took himself out after the poll was completed) have net negative ratings. Note they are also the most openly critical of Trump. The others are not known, rather than disliked. (The chart is sorted by % able to rate the candidate.)

DeSantis is the clear 2nd place for favorability among all Republicans, and has low unfavorable ratings as well. Pence has relatively high favorables but also unfavorables that are almost as high. With the launch of his presidential campaign, and apparent willingness to criticize Trump, at least in his kick-off speech, his break with Trump is now clearer.

But how do these Republicans who like Trump feel about the alternative candidates?

The next two charts shows favorability to each candidate among those Republicans who are favorable to Trump and among those unfavorable to Trump.

DeSantis jumps out in the “favorable to Trump” chart with especially strong ratings compared to the other candidates, while views of Pence are notable for the very close division in the party over him.

For Christie, those favorable to Trump are 18% favorable to Christie, 43% unfavorable (and 39% don’t have an opinion.) But those Republicans unfavorable to Trump don’t like Christie either! 17% fav, 38% unfav. So Christie doesn’t have am obvious strength among anti-Trump Republicans. Or, basically, anywhere in the GOP.

Compare DeSantis who is 67% fav and 12% unfav among those favorable to Trump, and 37-26 among those unfavorable to Trump. DeSantis’s strength is WITHIN the pro-Trump GOP, not really so much in the anti-Trump quarter of the party. That means DeSantis is a danger to Trump from “inside the house.” He would benefit if Trump voters started looking for an alternative. The trick of course is how does DeSantis make this happen without turning the pro-Trump folks against himself.

DeSantis’ appeal to pro-Trump Republicans looked especially strong earlier. He got increasingly favorable ratings among those favorable to Trump until recently. In our May data his favorability dropped sharply among those favorable to Trump as Trump’s criticism of DeSantis mounted. Yet DeSantis has never been especially popular with the anti-Trump wing of the party, so he can’t turn to them for a boost, at least not yet. Does his favorability continue down, especially if they go after one another? Can DeSantis actually hurt Trump’s standing with GOP voters?

This is where Christie could potentially help DeSantis or other single-digit candidates. He can criticize Trump without worrying about hurting himself because he is already so unpopular with all kinds of GOP voters. He could do the dirty work for DeSantis & Co. But would Christie’s criticism be effective when so many in the party have turned against him?

And consider Mike Pence. The second best known candidate divides the party sharply, with only a slightly net-favorable rating. Interestingly those favorable to Trump are also pretty favorable to Pence, despite Trump’s view of his former Vice-President. Should Pence take ths offensive against Trump he might carry more weight than the disliked Christie. But as with DeSantis, how can he turn GOP voters against Trump without creating self-inflicted wounds?

Tables with values plotted in the charts are shown below.